In 2011, the then Vice President Joe Biden proclaimed that China’s rise isn’t America’s demise in an opinion article published in the New York Times. That amiability between the two nations ten years ago is hard to imagine today: in 2022, he announced a chip ban to thwart Chinese tech development, named China as a long-term national security threat, and talked of “China’s challenge.”

It is interesting that one year after Biden’s proclamation marks a reversal in US public opinion of China. According to Pew data, before 2012, generally more Americans held a favorable view of China than an unfavorable one. After 2012, that trend switched and continued until today, where unfavorable views of China reached historic highs.

With China, whether looking inward or outward, there is always a lens. Today’s Chinese citizens use VPN to see the world beyond the Great Firewall. Throughout much of history, the American public sees China through the media’s account, which has not always been consistent. In the early days of the People’s Republic of China, the media painted it as a rogue state endangering the world order. Nixon’s visit and the normalization of relations between the two countries assuaged the earlier attitude. The media became more approving of China’s progress — a view that was briefly disrupted by the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, but largely continued into the 2010s.

On the surface, it does not seem like there’s anything remarkable about the year 2012. Sure, it was the year Xi Jinping gained prominence in the Chinese Communist Party, but his authoritarian tendencies were not apparent yet (Biden talks of Xi’s cooperative attitude in his article). As such, I want to understand how the media is involved in the unexpected public opinion reversal through analyzing both what is covered and how topics are covered in the years around 2012.

I posit that it is both possible for the media portrayal to lead public opinion, and for public opinion to skew media portrayal. Analyzing whether the shift in choice of coverage and angle of coverage occurred before or after 2012 will allow me to say with higher certainty that one trend precedes the other and that a correlation exists. Of course, this would not allow me to prove the existence of a causal relationship, but understanding how the media influences public opinion would be an enlightening demonstration of the power of media coverage.

In order to answer the question, I looked at print publications with traditionally different angles of reporting: the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Time magazine, and the Financial Times. I analyzed coverage via Google searches with specific domains, 1-year time range, and key words that involve China.

Through doing so, I have made the following key findings:

- Before 2009, coverage of China in the military context was scant. This started to change around 2011, and by 2012-2013, coverage of the Chinese military exploded. The Wall Street Journal noted the Chinese navy expansion, and the New York Times picked up on China’s cybersecurity threat in 2013.

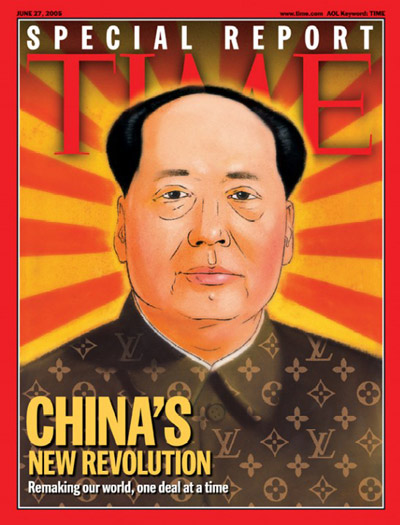

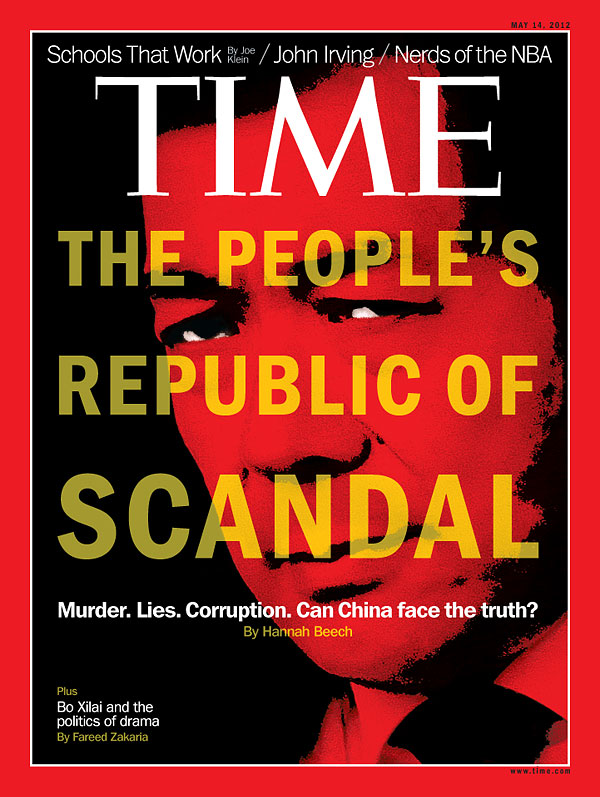

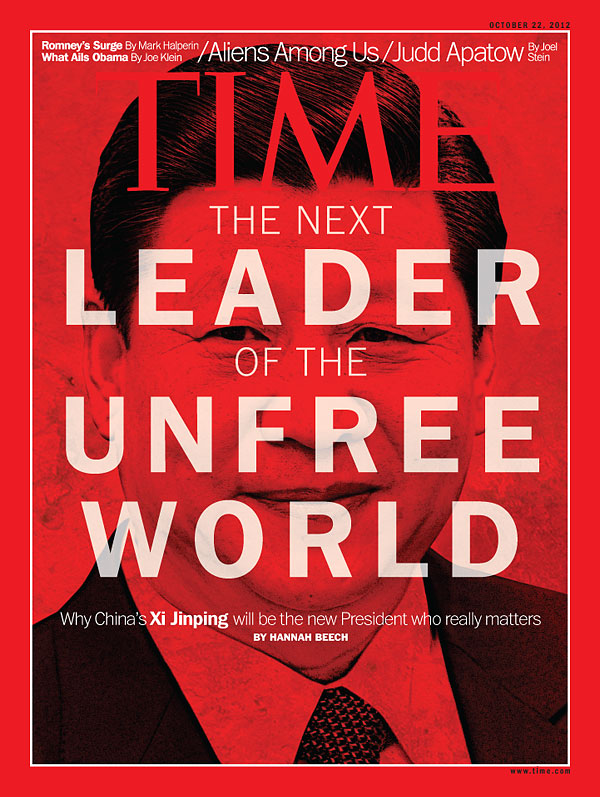

- China appeared on the cover of Time magazine five times in the period from 2005 to 2013. The two in 2005 and 2011 carried a tone of fascination, whereas the three after 2011 were more significantly more negative.

- Around 2010, the Financial Times started reporting the more restrictive policies in China, and business exits from China, a change from earlier era’s emphasis on the business opportunities in China.

- The New York Times coverage of the Tibetan protests that lasted from 2008 to 2012 show a change in tone and positioning that was growingly critical of the Chinese government.

- In international relations, coverage of China’s conflicts with its neighbors increased around 2010.

These findings suggest that there is both a change in what is covered and how they are covered in mainstream print media. Because the shifts seem to be occurring before the 2012 reversal in public opinion, there is reason to believe that the media might have played a role in leading American views of China.

Before 2010 and 2012 respectively, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times did not cover the Chinese military. Before 2008, the New York Times coverage of the Chinese military was both limited and matter of fact: in 2008, it covered the Chinese military in context of the deadly Sichuan earthquake.

After 2009, more stories about conflicts started appearing. The Times briefly covered a South China Sea incident between the US and Chinese navy. While giving a voice to both sides, the coverage painted China as more confrontational, with words such as China “lashed out” at the US. In 2010, the Times published stories about the expansion of Chinese naval power, but it rationalized the Chinese military’s new assertiveness with its “inexperience on the world stage” and remains optimistic that “renewed cooperation” will lead to better outcomes.

While its prior coverage of China focused on the Chinese economy, the Wall Street Journal started publishing more stories about China’s military advancements after 2011: new stealth fighter (2011), new destroyer (2012), new heavy military transport plane (2013), and multiple stories about the new aircraft carrier (2012). This is a stark contrast from earlier periods, as deployments of Chinese nuclear submarines were not covered.

The increased exposure of China’s military advancements is coupled with increased reporting of China’s military ambition. In 2011, a story about China’s naval presence in Indian Ocean; in 2012, a detailed article about China’s military catchup to the US; in 2013, coverage of “The China Dream” in military context — all of these portray China no longer as a regional power in East Asia and trade partner of the US, but more as a rising power with global ambitions and rapid development. With this shift in coverage, the Wall Street Journal was pursuing a different path for depicting China. Instead of thinking of China as just another part of the world, it is giving China more emphasis and pronouncing its capabilities and thus its potential threat.

In 2013, the New York Times covered the Chinese military-backed cyber attacks extensively. Said to be conducted by a unit of the People’s Liberation Army, the direct attack targeted US government computers, defense contractors, and the Times itself. The extensive coverage that spanned several stories meant wider circulation of the news, which likely alarmed the general public about a malicious China. The news posed China differently, as a rival to be contended with, as a problem that the US has set aside for too long and requires attention (the article noted how this is a remarkable criticism from the Pentagon, which previously avoided accusing the Chinese government or military for using cyberweapons for deliberate action).

Thus, there is a clear increase in coverage of Chinese military capability that started in 2011. While not doing so explicitly, the media implicitly point to the potential of the Chinese threat by choosing to tell stories about Chinese military programs and ambitions. It is important to note that before 2011, China did launch new weapons, modernize its military, and originate cyber attacks — but those news slipped through the US media lens. The revelation of such activities, perhaps for the first time for many Americans, would logically lead Americans to see China as beyond an economic powerhouse, be more wary of China, question Chinese intentions, and thus, view China less favorably.

Time magazine, published weekly with the majority of its readership in the US, tells interesting stories through its covers. Some of its covers have been iconic and greatly influential. Due to the composition of its readership, many of its covers reflect domestic issues, which makes its relatively limited covers about foreign issues especially valuable. The portrayal of China on the cover of Time magazine changed in 2011, closely correlated to the public opinion reversal that Pew observes.

In the 2000s, China was not frequently featured on the covers of Time. The June 27, 2005 issue, titled “China’s New Revolution,” shows the official portrait of Mao Zedong dressed in a Louis Vuitton coat. The cover story underlines China’s status as the world factory, its economic rise, and its agenda for stability. It tells the story of how economic performance would lead to political stability, and then it's all fun for everyone involved — the Chinese factory workers, the Chinese government, the US, everyone else.

In October 2011, the cover of a child blowing a Chinese-flag-colored bubble, titled “The China Bubble,” had a similar narrative. The article leads with China's economic miracle that materialized in the luxuries enjoyed by the Chinese nouveau riche, then compares it to the poor economic situation that Western countries found themselves in. Multinational corporations are excited to expand in China in a move tagged by the article as “the reverse Marco Polo.” Judging from what Time chose to report, enthusiasm about China seems to be at an all time high.

But it all came to an abrupt stop. In 2012, the two covers that involved China were much more negative. On May 14, 2012, the cover was the face of Bo Xilai painted in red — with the title “The People’s Republic of Scandal.” Bo was a contender for the top spot in the Communist Party who lost to Xi Jinping, with rumors circulating that he had intentions to stage a coup. The cover story exposed that piece of political drama, with insights about the corruption and crimes within the Party.

The October 22 cover echoed the previous one: this time Xi Jinping’s portrait is filtered with red. The title read “The Next Leader of the Unfree World.” In the article, the focus was the beaten hopes that China would continue to liberalize. Even though the article could not see into the future about Xi’s authoritarian reign, the sensational cover showed a clear change in attitude.

The June 17 cover in 2013 is a culmination of the change. The article chose to cover the cultural, political, and military ambitions of Xi’s China. The cover’s title, “The World According to China,” depicts an otherness, an inherent conflict of viewpoints — the sense that China carries a foreign agenda.

Altogether, the Time covers post-2011 recounted political drama and corruption, emphasized China’s political and ideological differences from the US, and positioned stories through an angle of an ambitious China’s rise. Through shifts in tone and perspective, it reminded its American audience that China is not just the glimmering economic miracle that its prior coverage revealed, but also an ideological outcast that is growing stronger. Because the change in Time’s attitude occurred right around 2011, it might have negatively affected the public opinion of China and contributed to the reversal in views of China.

One of the sources of instability in China in the late 2000s was the protest in Tibet, in response to both racial tension and government policies. When protests erupted in 2008, the Wall Street Journal positioned the issue as partly fueled by classist struggle amongst the Tibetans. Instead of placing much scrutiny on the government response to the protests or treatment of protestors, it delineated how the split between those who cooperated with the government, who believe that “Lhasa has developed so much since the 1970s,” and those who did not, who “detest [the Tibetans] who got educated in the Han system and then turned their backs on [them].” By focusing on the wealth gap and patriotism, the Journal coverage excused the government’s role in prompting the protests and played down the crackdown that ensued.

Both the Journal and the New York Times posed the issue more like a riot in 2008. The Times initial coverage emphasized violence both against the police and potentially to the people. By showing that soldiers died, that Tibetans were “beating Chinese residents with iron rods,” that mobs “set fire to a police car and a store owned by a Chinese shopkeeper,” and by ending the story with how a Chinese family feared for their safety, the article seems to sympathize with the Chinese locals and the police and paint the protesters as violent. A similar portrayal was in its inside look at Tibet, published several days later.

When discussing the crackdown that ensued, the Times took the angle of growing nationalism in China. By quoting the nationalist sentiment of Meng Huizhong, the article presented a government whose hands were tied by nationalism, whose decision to crack down on the protests was motivated by the concern for its electorate. While the article talked about how the Chinese Communist Party’s extensive nationalist propaganda of the past was to blame, it ascribes less agency to the government. For the American reader in 2008, the coverage of violent protests and rationalization for the government might have meant that they would find the Chinese people sympathetic and the government’s actions reasonable.

As the issue dragged on to 2012, however, the New York Times coverage was different. The Chinese government was directly placed at fault for the self-immolations in Tibet, by stating that school policies “incited” protests and describing the “monastic management” plan of the government. This was already different from prior coverage that did little to explain government policy that might have caused protests. Furthermore, the vivid description of the scene of Tsering Kyi’s self-immolation and the treatment of the monks likely attracted sympathy for them and antipathy for the government.

The crackdown was also covered differently in 2012 by the Times. The sources are more critical of the Chinese government. The unrest was seen as a struggle against “Chinese repression of political and religious freedoms.” The Chinese forces were shown “firing on and killing some demonstrators.” Deaths were described on both the Tibetan side and the Han Chinese and police side. The government was portrayed using “intimidating tactics to make sure information isn’t disseminated.” Overall, the article depicted the government’s firm hand in a ruthless, organized crackdown — very different from the 2008 depiction of “wavering” government forces.

Consequently, there is a clear shift in positioning that the New York Times adopted between 2008 and 2012. The clear sympathy with Tibetans and clear illustration of government ill-doings likely painted a worse image of China for Americans, especially as the coverage sparked memories of the 1989 crackdown.

Another interesting facet was how China’s conflicts with its neighbors were covered. The New York Times covered China’s activity in the South China Sea, in 2010 with Vietnam and 2012 with the Philippines. The difference in coverage is clear from the headlines: “Vietnam Seeks Negotiating Partners in Conflict With China Over Islands” versus “Beijing Projects Power in Strategic South China Sea.” One places Vietnam as the subject, the other Beijing. One shows negotiations in progress, the other shows China actively projecting power.

The 2010 article centered around Vietnam’s attempts in enlisting international support to limit China’s reach. The 2012 article, however, used the conflict between China and the Philippines as a proxy for China posing a challenge for the US. An ex-Filipino official was quoted as saying “China is testing the United States,” and a Chinese official was quoted dismissing any legitimate role of the US in the South China Sea.

Both issues were about Chinese claims in the South China Sea, but the different angles of coverage left different impressions for the audience: one of China as a regional power, one of China as a challenger of US primacy. Similar to increased coverage of the Chinese military, the change in framing here might have worsened China’s image for the American audience, as the unyielding and aggressive side of China comes into view.

All the above changes occurred around 2011 and 2012, which is generally before the public opinion reversal documented by Pew. Consequently, it is more likely that the shift in media coverage led to souring public opinion rather than being pulled by public opinion.

The choice of coverage is especially important for foreign issues, simply because of how few articles there are. For instance, the conflict between China and Vietnam in 2010 amounted to a single article in the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal had little to nothing to say about the Tibetan unrest after 2009. Thus, it is very likely that the choice and framing of coverage of foreign countries significantly impacts the general public’s conception of places such as China, particularly in the early 2010s when mainstream media was still most people’s main news source.

As to why the media changed its tone and choice of coverage, I have several hypotheses. First is a shift in leadership style, from the dissonant leadership of President Hu Jintao to the iron fist of President Xi Jinping. China did become more forceful in international relations, more unafraid to show off its military, more firm in its pursuit of a security state. Second might be the US media’s disillusion by the broken prospects of further reform and opening. China opened access to the New York Times website in 2001 under President Jiang Zeming, a signal of potential relaxation of rules on the media and civil society. However, it re-blocked access in 2012, seemingly on a whim. After many years of amicable waiting for a freer China and more transparent regime, perhaps the optimism wore off.

Either way, the shifts in media perspective is clear. With the change in coverage and tone, it is not surprising that Americans would see a new China — corrupt, cruel, ambitious — rather than the old portrayal — land of opportunity and economic growth.